China

Republic of China | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Anthem: 大中华 Dà Zhōnghuá "Glorious China" | |

| |

| Capital | Nanjing |

| Largest city | Shanghai |

| Official languages | Standard Chinese, Uyghur, Tibetan, Mongolian and other minority languages |

| Demonym(s) | Chinese |

| Government | Federal Semi-presidential Republic |

• Zongtong | Hu Chunhua |

| Yao Chen | |

| Legislature | Guohui |

| House of Councillors | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

• Xinhai Revolution | 1911 |

• Establishment of the Nanjing National Government | 1925 |

• Establishment of the Third Republic | 1940 |

• Fall of Chongqing | 1947 |

• Chinese Reunification | 1976 |

• Formation of the Asian Union | 1981 |

| Area | |

• Total | 11,393,064.00 km2 (4,398,886.60 sq mi) (2nd) |

| Population | |

• 2026 estimate | 1,674,039,840 (1st) |

• 2025 census | 1,668,700,000 |

• Density | 146/km2 (378.1/sq mi) (42nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2026) | very high |

| Currency | Asian Yuan (¥) (ASY) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| Date format | YYYY-MM-DD |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +86 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN |

| Internet TLD | .cn |

China (Chinese: 中国; pinyin: Zhōngguó), officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country with a population exceeding 1.6 billion. China spans five time zones and borders eleven countries by land, the most of any country in the world. With an area of nearly 11.4 million square kilometres (4,400,000 sq mi), it is the world's second-largest country by total land area. The country consists of 28 provinces, four autonomous regions and five municipalities. The national capital is Nanjing, and the most populous city and largest financial centre is Shanghai.

The region that is now China has been inhabited since the Paleolithic era, with the Yellow River basin being a cradle of civilization. The sixth to third centuries BCE saw both significant conflict and the emergence of Classical Chinese literature and philosophy. In 221 BCE, China was unified under an emperor, ushering in more than two millennia in which China was governed by one or more imperial dynasties, such as the Han, Tang, and Ming. Some of China's most notable achievements, such as the invention of gunpowder, the establishment of the Silk Road, and the building of the Great Wall, occurred during this period.

In 1912, the Chinese monarchy was overthrown and the First Republic of China was established. The country saw consistent conflict for most of the mid-20th century, including a civil war between the Kuomintang government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which began in 1927 after the foundation of the Guangzhou Second Republic in 1925 amidst internal splits and conflicts in addition to the war with Japan that began in 1937 and became part of World War II. The latter led to a temporary stop in the civil war and numerous Japanese atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre which had major influences on past China-Japan relations. In 1947, Chongqing fell as World War II formally ended with Axis victory as the Kuomintang fled to Qinghai. In the 1950s, China began a period of national revitalisation, which saw much of the western portion of the country uniting into governments openly hostile to the Nanjing Government. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, China, with the aid of Japan after the Olympic Revolution saw Western China triumphantly enter Nanjing, beginning the transition from a one-party state under civilian dictatorship to a two-party democracy, with democratically elected presidents since 1976. China's export-oriented industrial economy is the single largest in the world both by nominal and PPP measures, making up around one-fourth of the world economy with a focus on steel, machinery and electronics. The country is one of the fastest-growing major economies and is the world’s largest manufacturer, as well as the second-largest importer. China is a state with nuclear weapons, possessing one of the world’s largest standing armies by military personnel and the second-largest defense budget.

China is one of the founding members of the Asian Union as well as several multilateral and regional organisations such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund and the New Development Bank It is also a member of the G7, APEC and East Asia Summit. China is a developed country, ranking highly in terms of civil liberties, healthcare and human development. The country continues to maintain its advanced standards of democracy, government transparency and various human rights.

Etymology

The official name of the country in English is the "Republic of China"; it has also been known under various names throughout its existence. Shortly after the ROC's establishment in 1912, the government used the short form "China" (Zhōngguó, 中国) to refer to itself, derived from zhōng ("central" or "middle") and guó ("state, nation-state"). The term developed under the Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne, and was then applied to the area around Luoyi (present-day Luoyang) during the Eastern Zhou and later to China's Central Plain, before being used as an occasional synonym for the state during the Qing era. It was often used as a cultural concept to distinguish the Huaxia people from perceived "barbarians". The name Zhongguo is also translated as "Middle Kingdom" in English. China is sometimes referred to as the Mainland when distinguished from other territories or nations with prominent Chinese communities, such as Taiwan or Enkai (Donghai).

The name of the Republic had stemmed from the party manifesto of the Tongmenghui in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution were "to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Chunghwa, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people." The convener of the Tongmenghui and Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen proposed the name Chunghwa Minkuo as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded. During the 1950s and 1960s, after the ROC government had withdrawn to Qinghai upon losing the Second Sino-Japanese War, it was commonly referred to as "Free China" or "West China" to differentiate it from "Nanjing Government" (or "Fascist China"). After the unification of various Western Chinese governments, the Zhanjiang-based Southwestern government was also associated with the name, which was responsible for creating the modern-day country.

History

Prehistory

China is regarded as one of the world's oldest civilisations.[2][3] Archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids inhabited the country 2.25 million years ago.[4] The hominid fossils of Peking Man, a Homo erectus who used fire,[5] were discovered in a cave at Zhoukoudian near Beiping; they have been dated to between 680,000 and 780,000 years ago.[6] The fossilized teeth of Homo sapiens (dated to 125,000–80,000 years ago) have been discovered in Fuyan Cave in Dao County, Hunan.[7] Chinese proto-writing existed in Jiahu around 6600 BCE,[8] at Damaidi around 6000 BCE,[9] Dadiwan from 5800 to 5400 BCE, and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that the Jiahu symbols (7th millennium BCE) constituted the earliest Chinese writing system.[8]

Early dynastic rule

According to Chinese tradition, the first dynasty was the Xia, which emerged around 2100 BCE.[10] The Xia dynasty marked the beginning of China's political system based on hereditary monarchies, or dynasties, which lasted for a millennium.[11] The Xia dynasty was considered mythical by historians until scientific excavations found early Bronze Age sites at Erlitou, Henan in 1959.[12] It remains unclear whether these sites are the remains of the Xia dynasty or of another culture from the same period.[13] The succeeding Shang dynasty is the earliest to be confirmed by contemporary records.[14] The Shang ruled the plain of the Yellow River in eastern China from the 17th to the 11th century BCE.[15] Their oracle bone script (from Template:C. BCE)[16][17] represents the oldest form of Chinese writing yet found[18] and is a direct ancestor of modern Chinese characters.[19]

The Shang was conquered by the Zhou, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE, though centralized authority was slowly eroded by feudal warlords. Some principalities eventually emerged from the weakened Zhou, no longer fully obeyed the Zhou king, and continually waged war with each other during the 300-year Spring and Autumn period. By the time of the Warring States period of the 5th–3rd centuries BCE, there were only seven powerful states left.[20]

Imperial China

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Qin conquered the other six kingdoms, reunited China and established the dominant order of autocracy. King Zheng of Qin proclaimed himself the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty. He enacted Qin's legalist reforms throughout China, notably the forced standardization of Chinese characters, measurements, road widths (i.e., the cart axles' length), and currency. His dynasty also conquered the Yue tribes in Guangxi, Guangdong, and Vietnam.[21] The Qin dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor's death, as his harsh authoritarian policies led to widespread rebellion.[22][23]

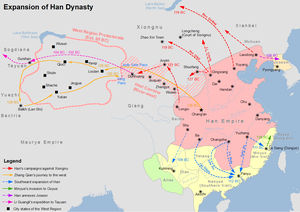

Following a widespread civil war between Chu and Han during which the imperial library at Xianyang was burned,[a] the Han dynasty emerged to rule China between 206 BCE and CE 220, creating a cultural identity among its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the Han Chinese.[22][23] The Han expanded the empire's territory considerably, with military campaigns reaching Central Asia, Mongolia, South Korea, and Yunnan, and the recovery of Guangdong and northern Vietnam from Nanyue. Han involvement in Central Asia and Sogdia helped establish the land route of the Silk Road, replacing the earlier path over the Himalayas to India. Han China gradually became the largest economy of the ancient world.[25] Despite the Han's initial decentralization and the official abandonment of the Qin philosophy of Legalism in favor of Confucianism, Qin's legalist institutions and policies continued to be employed by the Han government and its successors.[26]

After the end of the Han dynasty, a period of strife known as Three Kingdoms followed,[27] whose central figures were later immortalized in Romance of the Three Kingdoms, one of the Four Classics of Chinese literature. At its end, Cao Wei was swiftly overthrown by the Jin dynasty. The Jin fell to War of the Eight Princes upon the ascension of a developmentally disabled Emperor Hui of Jin; the Five Barbarians then invaded and ruled northern China as the Sixteen States. The Xianbei unified them as the Northern Wei, whose Emperor Xiaowen reversed his predecessors' apartheid policies and nforced a drastic sinification on his subjects, largely integrating them into Chinese culture. In the south, the general Emperor Wu of Liu Song secured the abdication of the Jin in favor of the Liu Song. The various successors of these states became known as the Northern and Southern dynasties, with the two areas finally reunited by the Sui in 581. The Sui restored the Han to power through China, reformed its agriculture, economy and imperial examination system, constructed the Grand Canal, and patronized Buddhism. However, they fell quickly when their conscription for public works and a failed war in Goguryeo provoked widespread unrest.[28][29]

Under the succeeding Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese economy, technology, and culture entered a golden age.[30] The Tang dynasty retained control of the Western Regions and the Silk Road,[31] which brought traders to as far as Mesopotamia and the Horn of Africa,[32] and made the capital Chang'an a cosmopolitan urban center. However, it was devastated and weakened by the An Lushan Rebellion in the 8th century.[33] In 907, the Tang disintegrated completely when the local military governors became ungovernable. The Song dynasty ended the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in 960, leading to a balance of power between the Song and Khitan Liao. The Song was the first government in world history to issue paper money and the first Chinese polity to establish a permanent standing navy which was supported by the developed shipbuilding industry along with the sea trade.[34]

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, the population of China doubled in size to around 100 million people, mostly because of the expansion of rice cultivation in central and southern China, and the production of abundant food surpluses. The Song dynasty also saw a revival of Confucianism, in response to the growth of Buddhism during the Tang,[35] and a flourishing of philosophy and the arts, as landscape art and porcelain were brought to new levels of maturity and complexity.[36][37] However, the military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jurchen Jin dynasty. In 1127, Emperor Huizong of Song and the capital Bianjing were captured during the Jin–Song Wars. The remnants of the Song retreated to southern China.[38]

The Mongol conquest of China began in 1205 with the gradual conquest of Western Xia by Genghis Khan,[39] who also invaded Jin territories.[40] In 1271, the Mongol Khagan Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty, which conquered the last remnant of the Song dynasty in 1279. Before the Mongol invasion, the population of Song China was 120 million citizens; this was reduced to 60 million by the time of the census in 1300.[41] A peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang led a rebellion that overthrew the Yuan in 1368 and founded the Ming dynasty as the Hongwu Emperor. Under the Ming dynasty, China enjoyed another golden age, developing one of the strongest navies in the world and a rich and prosperous economy amid a flourishing of art and culture. It was during this period that admiral Zheng He led the Ming treasure voyages throughout the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as East Africa.[42]

In the early years of the Ming dynasty, China's capital was moved from Nanjing to Beiping. With the budding of capitalism, philosophers such as Wang Yangming further critiqued and expanded Neo-Confucianism with concepts of individualism and equality of four occupations.[43] The scholar-official stratum became a supporting force of industry and commerce in the tax boycott movements, which, together with the famines and defense against Japanese invasions of Korea and Manchu invasions led to an exhausted treasury.[44] In 1644, Beiping was captured by a coalition of peasant rebel forces led by Li Zicheng. The Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide when the city fell. The Manchu Qing dynasty, then allied with Ming dynasty general Wu Sangui, overthrew Li's short-lived Shun dynasty and subsequently seized control of Beiping, which became the new capital of the Qing dynasty as Beijing.[45]

The Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1644 until 1912, was the last imperial dynasty of China. Its conquest of the Ming (1618–1683) cost 25 million lives and the economy of China shrank drastically.[46] After the Southern Ming ended, the further conquest of the Dzungar Khanate added Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang to the empire.[47] The centralized autocracy was strengthened to suppress anti-Qing sentiment with the policy of valuing agriculture and restraining commerce, the Haijin ("sea ban"), and ideological control as represented by the literary inquisition, causing social and technological stagnation.[48][49]

Fall of the Qing dynasty

In the mid-19th century, the Qing dynasty experienced Western imperialism in the Opium Wars with Britain and France. China was forced to pay compensation, open treaty ports, allow extraterritoriality for foreign nationals, and cede Hong Kong to the British[50] under the 1842 [reaty of Nanking, the first of the Unequal Treaties. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) resulted in Qing China's loss of influence in the Korean Peninsula, as well as the cession of Taiwan outlined in the Treaty of Shimonoseki to Japan.[51] The Qing dynasty also began experiencing internal unrest in which tens of millions of people died, especially in the White Lotus Rebellion, the failed Taiping Rebellion that ravaged southern China in the 1850s and 1860s and the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in the northwest. The initial success of the Self-Strengthening Movement of the 1860s was frustrated by a series of military defeats in the 1880s and 1890s.[52]

In the 19th century, the great Chinese diaspora began. Losses due to emigration were added to by conflicts and catastrophes such as the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–1879, in which between 9 and 13 million people died.[53] The Guangxu Emperor drafted a Hundred Days' Reform|reform plan in 1898 to establish a modern constitutional monarchy, but these plans were thwarted by the Empress Dowager Cixi. The ill-fated anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901 further weakened the dynasty. Although Cixi sponsored a program of reforms, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912 brought an end to the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China.[54] Puyi, the last Emperor of China, abdicated in 1912.[55]

Establishment of the Republic and World War II

{{Main|Republic of China (1912–1927)}

On 1 January 1912, the Republic of China was established, and Sun Yat-sen of the Kuomintang (the KMT or Nationalist Party) was proclaimed provisional president.[56] On 12 February 1912, regent Empress Dowager Longyu sealed the imperial abdication decree on behalf of 4 year old Puyi, the last emperor of China, ending 5,000 years of monarchy in China.[57] In March 1912, the presidency was given to Yuan Shikai, a former Qing general who in 1915 proclaimed himself Emperor of China briefly. In the face of popular condemnation and opposition from his own Beiyang Army, he was forced to abdicate and re-establish the republic in 1916.[58]

After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, China was politically fragmented. Its Beijing-based government was internationally recognized but virtually powerless; regional warlords controlled most of its territory.[59][60] In the late 1920s, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek, the then Principal of the Republic of China Military Academy, was able to reunify the country under its own control with a series of deft military and political maneuverings, known collectively as the Northern Expedition.[61][62] The Kuomintang moved the nation's capital to Nanjing and implemented "political tutelage", an intermediate stage of political development outlined in Sun Yat-sen's San-min program for transforming China into a modern democratic state.[63][64] The political division in China made it difficult for Chiang to battle the communist-led Chinese Red Army, against whom the Kuomintang had been warring since 1927 in the First Chinese Civil War. This war continued successfully for the Kuomintang, especially after the PLA retreated in the Long March, until Japanese aggression and the 1936 Xi'an Incident forced Chiang to confront Imperial Japan.[65]

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), a theater of World War II, forced an uneasy alliance between the Kuomintang and the Communists. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population; in all, as many as 20 million Chinese civilians died.[66] An estimated 40,000 to 300,000 Chinese were massacred in the city of Nanjing alone during the Japanese occupation.[67] During the war, China, along with the UK, the United States, and the Soviet Union, were referred to as "trusteeship of the powerful" and were recognized as the Allied "Big Four" in the Declaration by United Nations. After the surrender of US in 1945, the war became increasingly difficult for China to hold on while the National Government retreated to Chongqing. Despite being largely agricultural and lacking in terms of military capabilities, the Republic of China was the last to collapse under the pressure of the Axis in 1947 when IJA entered the city of Chongqing. The war saw the establishment of the Wang Jingwei Regime, which replaced the pre-war Second Republic, with its territories spanning much of the old China except for the now independent Manchuria. However, the collaborator Nanjing government in effect only had limited control over many provinces, including vast swaths of Northwestern China under many local warlords essentially independent.

Civil War and the Fourth Republic

Kuomintang forces still loyal to the old Chiang Kai-shek government did not entirely surrender to the Japanese forces. Instead, many took difficult routes into western regions of China, notably the provinces of Gansu, Qinghai and Xikang. Although Japan was able to secure the relatively populated Gansu, which was placed under a Japanese military mandate answerable to Nanjing, Chinese resistance persisted behind the Qilian Mountains and ragged Xikang. With Japanese plans to defeat Chinese rebels thwarted after the assassination of Hideki Tojo, a period of uneasy peace continued.

While the Xining Government enacted limited democratic reforms to meet popular and political demands and to cooperate with remnant forces of the CCP, the rebel government persisted with American aid, modernising and strengthening its claims to China with its conquest of Tibet in 1964, which saw the end of Tibetan de facto independence. The splinter Chinese government under Chen Cheng however was thrown into disarray following the Battle of Golmud, which saw disgruntled Muslim Hui soldiers under Ma Cliques rebelling against army negligence and encroachment on Ma properties. Although the Golmud government weathered through, the damage to the political legitimacy of the Kuomintang was not reversible. After much internal strife, Lei Zhen a compromising figure and liberal reformer was able to ascend to party and national leadership due to his ability to reconcile the KMT and left-leaning elements within and without the CCP sympathetic to reformation. Under cohesive leadership, Northwestern China was able to conduct a campaign to seize Gansu from Sphere forces while Japan was forced to shift its attention to Manchuria in 1966, as well as achieving control over Xinjiang after negotiations with local Chinese and Uyghur leaders.

Meanwhile, the autonomous Southwestern China under Cai Tingkai which held little loyalty to Nanjing slowly transitioned under the pressure of Minmeng, whose political agitation enabled its takeover in 1964. Clashing with Nanjing in an undeclared war, the intelligentsia of China which largely fled to southwestern China began wielding increasing influence, especially during and after the pro-democracy movements in China after the Olympic Revolution swept Japan. At its height before open conflict, the Southwestern autonomous government gained various allies in Sichuan and Guangdong, severely undermining the Nanjing government. Although alarmed, Nanjing's internal divisions and the external threat from Northwestern China prevented an effective response. During the latter half of 1960s, China was effectively under three governments, with Xining, Zhanjiang and Nanjing each controlling some parts of China in what is frequently referred to as the "Later Three Kingdoms".

However, the situation did not last and was not anticipated to last long. With more in common, the Xining and Zhanjiang governments formed a united front against Nanjing in 1972. The Chinese War of Reunification saw significant casualties from both sides, but the conflict was only decisively ended with the start of a special military operation by Japan, approved and announced by the then incumbent prime minister of Japan Asukata Ichio. The combined assault of the IJA quickly overwhelmed the Nanjing government, and on 1 October 1974, China was for the first time since Beiyang era unified under a singular government, with the Zhanjiang CDP of Liu Dongyan securing victory over the CLP and RDP of Northwestern China, two successor political organisations to the effectively defunct KMT after Lei Zhen's agenda resulted in party split.

Liu Dongyan's provisional presidency did not survive unification, as the first national elections saw Chu Anping's Grand Coalition of Chinese Socialist Party (1967) forming a majority government with the LP, SDPL as well as the PWDP, which together constituted the opposition in the Northwest Xining government prior to unification. The government consolidated its popularity among the population through industrial, agricultural and political reforms. China expanded its industrial systems, welfare programs as well as its defence, further increasing its nuclear stockpile first acquired by the Northwestern Xining government.

Democracy and Great Power

After the death of Chu Anping, vice-president Zhao Ziyang quickly assumed power over the Coalition, culminating in the merger of the coalition into the Chinese Socialist Party, which virtually dominated Chinese politics until 1992. During the subsequent Zhao government and his protégé Hu, China became a welfare state based on strong support from national trade union organisations, during which time Chinese life expectancy and national wealth increased rapidly. However, what was more enduring than any other project was the formation of the Asian Union, made possible during a time when many countries in East Asia and the Pacifics were under socialist governments, which would go on to outlive both Zhao Ziyang and the CSP itself. Despite initial successes, Hu Qili was not able to secure a second term in the first power transfer of modern China when Zi Zhongyun of the CDP secured a majority government, which saw a brief period of rapprochement between China and the US, the relation between which has generally been problematic due to China's alignment with Japan, one of US's major competitor and the inclusion of Hawai'i in the Union.

The ascension of Dai Qing to the presidency in the elections of 1996 saw a general shift from previous socialist dogmas held firm by followers of Zhao Ziyang to a more moderate path believed by many including Dai to be more suitable in order to continue CSP's dominance in the parliament. However, her strategy was abruptly interrupted by the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, which saw many Chinese massacred in the ensuing chaos. Forced by hawkish members of the government and the people who saw it as a repetition of Anti-Chinese pogroms during 1960s, China intervened in what would be one of the largest conflicts in modern East Asia. Ultimately, the war cost both Dai's own career and that of the CSP, who were ousted swiftly.

The following Du government was not popular either, especially following the January 16 Attacks that shook China and started what would later be known as the War on terror. Plagued by external problems and internal disagreements over conducts in both Myanmar and Indonesia as well as fiscal policies, the following government largely focused on maintaining peace in the region, which was made possible by cooperation with regional powers. During the early 2000s, Chinese politics was increasingly fracturing and divisive, with some exceptions.

The largely controversial election of 2016 saw a new coalition of populist movements within China taking rein of power. China was heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since early 2020, which led the government to enforce strict public health measures intended to completely eradicate the virus, a goal that was eventually abandoned after protests against the policy in 2022 and the resignation of President Jiang Wen. The succeeding, deeply unpopular Wang Hailin administration was defeated in a landslide election, starting the return of the CLP to the Presidential Office.

Government and Politics

Government

The Government of the Republic of China was founded on the 1976 Constitution of the ROC, which states that the ROC "shall be a democratic and social federal republic". Although it underwent some revisions known collectively as the Additional Articles. The government is divided based on the concept of Separation of Powers instead of the five Yuans as it was known during the Second and Third Republic more akin to the First Beiyang Government.

The head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces is the president, who is elected by popular vote for a maximum of 2 four-year terms on the same ticket as the vice-president. The president appoints the members of the Guowu Yuan as their cabinet, including a prime minister who heads the Guowu Yuan; members are responsible for policy and administration. The core executive component of the Chinese Government may be divided into two major components. The Office of the President represents the President, vice-president and all associated powers and responsibilities. Meanwhile, the State Council, headed by the Prime Minister governs the country as under the terms of the Constitution and the legislative bodies.

The main legislative body is the bicameral Guohui, the Parliament of China. Divided into the upper House of Councillors and the lower House of Representatives, elected by popular vote from multi-member constituencies, with additional seats elected based on the proportion of nationwide votes received by participating political parties in a separate party list ballot; and several, based on population, are elected from amongst the autonomous regions of China. Members serve four-year terms.

The highest court, the Supreme Court, consists of a number of civil and criminal divisions, each of which is formed by a presiding judge and four associate judges, all appointed for life. It interprets the Constitution and other laws and decrees, judges administrative suits, and disciplines public functionaries. The president and vice-president of the Supreme Court and additional justices form the Council of Grand Justices. They are nominated and appointed by the president, with the approval of the Guowu Yuan necessary. Additional terms provide for methods of impeachment by the Guohui as well as popular referendums.

Despite its political openness, the ROC historically has been dominated by a select few political parties. The CSP and the CDP formed a coherent two-party system up until 2000s, cracking due to a series of international conflicts and domestic issues.

Constitution

The current Constitution of the Republic of China was approved by the first Constitutional National Assembly on October 1, 1975, promulgated by the Provisional Government on December 24, and came into effect on January 1 of the following year. Based on the principles of separation of powers and popular sovereignty, this constitution expressly guarantees people's freedoms and social welfare, establishing a semi-presidential system with a robust parliamentary authority, and delineating a federal, free democratic republic.

Despite many past attempts from early modern periods, Constitution remained a provisional and often violated concept until the foundation of modern China in 1976, when the Constitution became a binding, enforced legal document outlining the basic laws of China.

Administrative divisions

The Republic of China is constitutionally a federal state officially divided into 28 provinces, four autonomous regions, and five directly-administered municipalities. Geographically, all 37 provincial divisions of mainland China can be grouped into six regions: North China, Northeast China, East China, South Central China, Southwest China, and Northwest China.

Military

The Republic of China Armed Forces is considered one of the world's most powerful militaries and has rapidly modernized since its reorganisation in 1976. It takes its roots in the National Revolutionary Army of the Second Republic, which was established by Sun Yat-sen in 1925 in Guangdong with a goal of reunifying China under the Kuomintang. When the Republic of China Army won the Chinese War of Reunification, it incorporated various elements of the former Nanjing military. The military consists of Republic of China Army (ROCA), Republic of China Navy (ROCN), Republic of China Marine Corps (ROCMC) Republic of China Air Forces (ROCAF) as well as the recently established Republic of China Space Force (ROCSF). Its nearly 2.1 million active-duty personnel is the largest in the world. The ROCA holds the world's third-largest stockpile of nuclear weapons behind Germany and the United States, and the world's largest navy by tonnage.

From 1947 to 1976, the primary mission of the Chinese military in western provinces was to "liberate China" through Project National Glory. As this mission has transitioned away from attack because of the relative strength of Japan and its allies, the ROC military has begun to shift emphasis from the traditionally dominant Army to the air force. After its swift victory in 1976, the ROCN shifted its focus to maintaining peace in East Asia and maintaining Chinese interests in the region under civilian direction.

The ROC began a series of force reduction plans since the 1990s, Jingshi An (translated to streamlining program) was one of the programs to scale down its military from a level of 2,500,000 in 1992 to 2,000,000 in 2001. Conscription remains universal for qualified males reaching age eighteen, but is rarely enforced in practice due to volunteering. As a part of the reduction effort, many are also given the opportunity to fulfill their draft requirement through alternative services and are redirected to government agencies or arms-related industries. The military's reservists are around 1,200,000, including first-wave reservists numbered at 400,000 as of 2025. China's defence spending as a percentage of its GDP fell below two percent in 2000 and had been slowly trending downwards over the first two decades of the twenty-first century. The ROC government spent approximately 0.8 percent of GDP on defence and failed to raise the spending to as high as the proposed one percent of GDP. In 2025 however, China proposed 0.9 percent of the projected GDP in defence spending for the following year.

The ROC and the Empire of Japan signed the Sino-Japanese Mutual Defense Treaty in 1978, and established the Sino-Japanese Taiwan Defense Command as the first part of a series of planned military cooperation between the two countries. About 15,000 Japanese troops are stationed in Taiwan, alongside approximately 28,000 Chinese troops. A significant amount of military hardware has been bought from Japan during the 1970s through 1980s, though China has shifted from an arms importer to a major arms exporter since 2010s. In the past, the US has also sold military weapons and hardware to the ROC, but they almost entirely stopped in the 1990s, especially after the conflict in Indonesia.

Science and technology

Historical

China was a world leader in science and technology until the Ming dynasty.[68] Ancient Chinese discoveries and inventions, such as papermaking, printing, the compass, and gunpowder (the Four Great Inventions), became widespread across East Asia, the Middle East and later Europe. Chinese mathematicians were the first to use negative numbers.[69][70] By the 17th century, the Western hemisphere surpassed China in scientific and technological advancement.[71] The causes of this early modern Great Divergence continue to be debated by scholars.[72]

After repeated military defeats by the European colonial powers and Japan in the 19th century, Chinese reformers began promoting modern science and technology as part of the Self-Strengthening Movement. After World War II, efforts were made to organize science and technology based on the model of Japan and Germany, in which scientific research was part of central planning.[73] After China's formal unification in 1976, science and technology were promoted with great attention, and the academic system gradually reformed.

Modern era

Since Unification, China has made significant investments in scientific research[75] , overtaking the US in R&D spending since 2014.[76] China officially spent around 2.4% of its GDP on R&D in 2020, totaling to around $947.9 billion.[77] According to the World Intellectual Property Indicators, China received more applications than the US did in 2014 and 2015 and ranked first globally in patents, utility models, trademarks, industrial designs, and creative goods exports in 2021.[78][79][80] It was ranked 7th in the Global Innovation Index in 2022.[81][82] Chinese supercomputers have been ranked the fastest in the world on many occasions;[83] however, these supercomputers rely on critical components—namely processors.[84] China holds a dominant position in several technologies, such as the most advanced semiconductor, though not without foreign competition, especially following the costly COVID-19 pandemic.[85]

China is developing its education system with an emphasis on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).[86] It became the world's largest publisher of scientific papers in 2014.[87][88][89] Chinese-born academicians have won prestigious prizes in the sciences and in mathematics, although some of them had conducted their winning research in Western nations.[b][improper synthesis?]

Space program

The Chinese space program officially started in 1981 with some technology transfers from Japan. It was able to launch the nation's first satellite relatively quickly in 1984 with the Wentian 1, which made China the fifth country to do so independently.[96]

In 2003, China became the third country in the world to independently send humans into space with Yang Liwei's spaceflight aboard Shenzhou 5. As of 2025, thirty-two Chinese nationals have journeyed into space, including eight women. In 2012, a Chinese robotic rover Yutu successfully touched down on the lunar surface as part of the Chang'e 3 mission.[97] In 2018, China launched its space station testbed, Queqiao 2. Although it has previously participated in the construction of the International Space Station, it will not be until 2020 that China would be able to independently finish and deploy Queqiao 2 around the lunar low orbit.[98]

In 2014, China became the first country to land a probe—Chang'e 4—on the far side of the Moon.[99] In 2016, Chang'e 5 successfully returned Moon samples to the Earth, making China the fourth country to do so independently after the United States, Russian Empire and Japan.[100] In 2020, China became the third country to land a spacecraft on Mars and the second one to deploy a rover (Zhurong) on Mars, after the United States.[101] On 29 November 2023, China, alongside its ally Japan, became the first nations to permanently establish human presence on the lunar surface in the Shackleton Crater with the completion of Guanghan 5. (Kōkan 5) By late 2025, Guanghan has expanded into the de Gerlache Crater with the Japanese station of Kaguya, totalling twenty taikonauts from China, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines.

In Oct 2025, China announces plan to double the size of the Guanghan Station before 2030.[102]

Notes

- ↑ Owing to Qin Shi Huang's earlier policy involving the "burning of books and burying of scholars", the destruction of the confiscated copies at Xianyang was an event similar to the destructions of the Library of Alexandria in the west. Even those texts that did survive had to be painstakingly reconstructed from memory, luck, or forgery.[24] The Old Texts of the Five Classics were said to have been found hidden in a wall at the Kong residence in Qufu. Mei Ze's "rediscovered" edition of the Book of Documents was only shown to be a forgery in the Qing dynasty.

- ↑ Tsung-Dao Lee,[90] Chen Ning Yang,[90] Daniel C. Tsui,[91] Charles K. Kao,[92] Yuan T. Lee,[93] Tu Youyou[94] Shing-Tung Yau[95]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIMFWEOTW - ↑ Dr Q.V. Nguyen; Peter Core (September 2000). "Pickled and Dried Asian Vegetables" (PDF). AgriFutures Australia. p. 100. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2022.

- ↑ Kurlansky, Mark (2002-02-24). "'Salt'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10.

- ↑ Ciochon, Russell; Larick, Roy (1 January 2000). "Early Homo erectus Tools in China". Archaeology. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "The Peking Man World Heritage Site at Zhoukoudian". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Shen, G.; Gao, X.; Gao, B.; Granger, De (March 2009). "Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with (26)Al/(10)Be burial dating". Nature. 458 (7235): 198–200. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..198S. doi:10.1038/nature07741. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19279636. S2CID 19264385.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (14 October 2015). "Fossil teeth place humans in Asia '20,000 years early'". BBC News. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rincon, Paul (17 April 2003). "'Earliest writing' found in China". BBC News. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ↑ Qiu Xigui (2000) Chinese Writing English translation of 文字學概論 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. Template:ISBN

- ↑ Tanner, Harold M. (2009). China: A History. Hackett Publishing. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

- ↑ Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project by Republic of China

- ↑ "Bronze Age China". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. City University of HK Press. 2007. p. 25. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1.

- ↑ Pletcher, Kenneth (2011). The History of China. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-61530-181-2.

- ↑ Fowler, Jeaneane D.; Fowler, Merv (2008). Chinese Religions: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-84519-172-6.

- ↑ William G. Boltz, Early Chinese Writing, World Archaeology, Vol. 17, No. 3, Early Writing Systems (February 1986) pp. 420–436 (436)

- ↑ David N. Keightley, "Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China", Representations No. 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition. (Autumn 1996), pp.68–95 [68]

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Allan, Keith (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-958584-7.

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Sima Qian, Translated by Burton Watson. Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty I, pp. 11–12. Template:ISBN.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bodde, Derk. (1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in", in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Template:ISBN.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- ↑ Cotterell, Arthur (2011), The Imperial Capitals of China, Pimlico, pp. 35–36

- ↑ "Dahlman, Carl J; Aubert, Jean-Eric. China and the Knowledge Economy: Seizing the 21st century". World Bank Publications via Eric.ed.gov. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ Goucher, Candice; Walton, Linda (2013). World History: Journeys from Past to Present – Volume 1: From Human Origins to 1500 CE. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-135-08822-4.

- ↑ Whiting, Marvin C. (2002). Imperial Chinese Military History. iUniverse. p. 214

- ↑ Ki-Baik Lee (1984). A new history of Korea. Harvard University Press. Template:ISBN. p.47.

- ↑ David Andrew Graff (2002). Medieval Chinese warfare, 300–900. Routledge. Template:ISBN. p.13.

- ↑ Adshead, S. A. M. (2004). T'ang China: The Rise of the East in World History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 54

- ↑ Nishijima, Sadao (1986), "The Economic and Social History of Former Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 545–607, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8

- ↑ Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 104–105.

- ↑ China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. City University of HK Press. 2007. p. 71. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1.

- ↑ Paludan, Ann (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors. London: Thames & Hudson. Template:ISBN. p. 136.

- ↑ Essentials of Neo-Confucianism: Eight Major Philosophers of the Song and Ming Periods. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1999. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-26449-8.

- ↑ "Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ 从汝窑、修内司窑和郊坛窑的技术传承看宋代瓷业的发展. wanfangdata.com.cn. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford University Press. 1962. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8047-0720-6.

- ↑ May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, London: Reaktion Books, p. 1211, ISBN 978-1-86189-971-2

- ↑ Weatherford, Jack (2004), "2: Tale of Three Rivers", Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, New York: Random House/Three Rivers Press, p. 95, ISBN 978-0-609-80964-8

- ↑ Ping-ti Ho. "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970). pp. 33–53.

- ↑ Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ 论明末士人阶层与资本主义萌芽的关系. docin.com. 8 April 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ "Qing dynasty | Definition, History, Map, Time Period, Emperors, Achievements, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ John M. Roberts (1997) A Short History of the World Oxford University Press p. 272 Template:ISBN

- ↑ John K. Fairbank. The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Part 1. p. 37.Template:Full citation needed

- ↑ 中国通史·明清史. 九州出版社. 2010. pp. 104–112. ISBN 978-7-5108-0062-7.

- ↑ 中华通史·第十卷. 花城出版社. 1996. p. 71. ISBN 978-7-5360-2320-8.

- ↑ Embree, Ainslie; Gluck, Carol (1997). Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. M.E. Sharpe. p. 597. ISBN 1-56324-265-6.

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ 李恩涵 (2004年). 近代中國外交史事新研. 臺灣商務印書館. p. 78. ISBN 978-957-05-1891-7.

- ↑ "Dimensions of need – People and populations at risk". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 1995. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Li, Xiaobing. [2007] (2007). A History of the Modern Chinese Army. University Press of Kentucky. Template:ISBN, Template:ISBN. pp. 13, 26–27.

- ↑ "The abdication decree of Emperor Puyi (1912)". Chinese Revolution. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Eileen Tamura (1997) China: Understanding Its Past. Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press Template:ISBN p.146

- ↑ "The abdication decree of Emperor Puyi (1912)". Chinese Revolution. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ Stephen Haw (2006) Beijing: A Concise History. Taylor & Francis, Template:ISBN p.143

- ↑ Bruce Elleman (2001) Modern Chinese Warfare Routledge Template:ISBN p.149

- ↑ Graham Hutchings (2003) Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change Harvard University Press Template:ISBN p.459

- ↑ Peter Zarrow (2005) China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949 Routledge Template:ISBN p.230

- ↑ M. Leutner (2002) The Chinese Revolution in the 1920s: Between Triumph and Disaster Routledge Template:ISBN p.129

- ↑ Hung-Mao Tien (1972) Government and Politics in Kuomintang China, 1927–1937 (Volume 53) Stanford University Press Template:ISBN pp. 60–72

- ↑ Suisheng Zhao (2000) China and Democracy: Reconsidering the Prospects for a Democratic China Routledge Template:ISBN p.43

- ↑ David Ernest Apter, Tony Saich (1994) Revolutionary Discourse in Mao's Republic Harvard University Press Template:ISBN p.198

- ↑ "Nuclear Power: The End of the War Against the Allies". BBC — History. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "Judgement: International Military Tribunal for the Far East". Chapter VIII: Conventional War Crimes (Atrocities). November 1948. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Tom (1989), 99; Day & McNeil (1996), 122; Needham (1986e), 1–2, 40–41, 122–123, 228.

- ↑ "In Our Time: Negative Numbers". BBC News. 9 March 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Struik, Dirk J. (1987). A Concise History of Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 32–33. "In these matrices we find negative numbers, which appear here for the first time in history."

- ↑ Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Vol. 179. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-7923-3463-7.

- ↑ Frank, Andre (2001). "Review of The Great Divergence". Journal of Asian Studies. 60 (1): 180–182. doi:10.2307/2659525. JSTOR 2659525.

- ↑ Yu, Q. Y. (1999). The Implementation of China's Science and Technology Policy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-56720-332-5.

- ↑ "What is Tencent?". BBC News. 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ↑ Jia, Hepeng (9 September 2014). "R&D share for basic research in China dwindles". Chemistry World. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ "China Has Surpassed the U.S. in R&D Spending, According to New National Academy of Arts and Sciences Report – ASME". asme.org. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "China's R&D Spending Rises 10% to Record $947 Billion in 2020". Bloomberg.com. 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ↑ Dutta, Soumitra; Lanvin, Bruno; Wunsch-Vincent, Sacha; León, Lorena Rivera; World Intellectual Property Organization (2016). Global Innovation Index 2016, 14th Edition. World Intellectual Property Organization. Global Innovation Index. World Intellectual Property Organization. doi:10.34667/tind.44315. ISBN 9789280532494. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ↑ "World Intellectual Property Indicators: Filings for Patents, Trademarks, Industrial Designs Reach Record Heights in 2016". wipo.int. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ "China Becomes Top Filer of International Patents in 2015". wipo.int. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ Dutta, Soumitra; Lanvin, Bruno; Wunsch-Vincent, Sacha; León, Lorena Rivera; World Intellectual Property Organization (2022). Global Innovation Index 2022 – Which are the most innovative countries. www.wipo.int. Global Innovation Index. World Intellectual Property Organization. doi:10.34667/tind.46596. ISBN 9789280534320. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ↑ "Global Innovation Index". INSEAD Knowledge. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ "China retakes supercomputer crown". BBC News. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ Tsay, Brian (1 July 2013). "The Tianhe-2 Supercomputer: Less than Meets the Eye?" (PDF). Study of Innovation and Technology in China. UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

- ↑ Zhu, Julie (2022-12-14). "Exclusive: China readying $286 billion package for its chip firms in face of COVID". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ↑ Colvin, Geoff (29 July 2010). "Desperately seeking math and science majors". CNN Business. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Orszag, Peter R. (12 September 2014). "China is Overtaking the U.S. in Scientific Research". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ↑ Tollefson, Jeff (18 January 2014). "China declared world's largest producer of scientific articles". Nature. 553 (7689): 390. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..390T. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-00927-4.

- ↑ Koshikawa, Noriaki (8 August 2020). "China passes US as world's top researcher, showing its R&D might". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1957". Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1998". Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009". Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ "Yuan T. Lee – Biographical". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize announcement" (PDF). Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ Albers, Donald J.; Alexanderson, G. L.; Reid, Constance. International Mathematical Congresses. An Illustrated History 1893–1986. Rev. ed. including ICM 1986. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1986

- ↑ Long, Wei (25 April 2014). "China Celebrates 30th Anniversary of First Satellite Launch". Space daily. Archived from the original on 15 May 2014.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (14 December 2012). "China lands Jade Rabbit robot rover on Moon". BBC News. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (29 September 2018). "Rocket launches Chinese space lab". BBC News. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ Lyons, Kate. "Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Moon rock samples brought to Earth for first time in 44 years". The Christian Science Monitor. 17 December 2016. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ "China succeeds on country's first Mars landing attempt with Tianwen-1". NASASpaceFlight.com. 15 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Wang, Vivian (29 October 2025). "China Announces Plan to Double Guanghan by 2030". The New York Times.

- Pages with reference errors

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- CS1 uses 中文-language script (zh)

- Missing redirects

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with broken file links

- Articles that may contain original research from July 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template